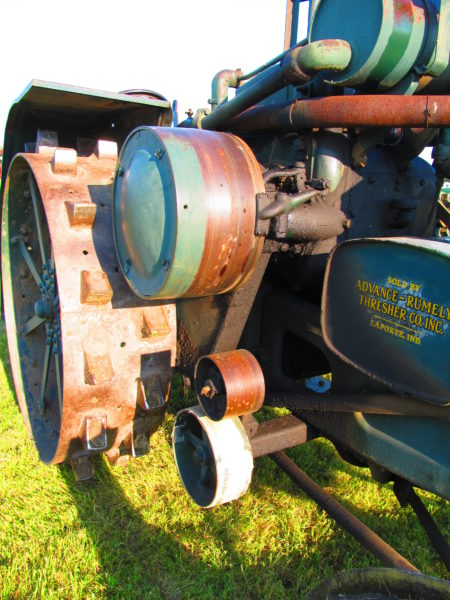

Rumely Model E at the Museum led an interesting life before being rescued from a scrap pile in the 1950s by Joseph Tucker of Portage la Prairie and the Menshall Brothers of Pierson, Manitoba. Since that time it has been a resident at the Museum.

The Model E was purchased new in 1912 by an American named Olmstead who shipped it to Pierson, Manitoba where it broke land and custom threshed. Local legend has it that the tractor wore out five sets of gears during its working life. In 1922 the Burns Brothers purchased the tractor and used it to thresh until 1928. At some point after that it was sold to a scrap dealer in Carievale, Saskatchewan where Mr Tucker and the Menshall Brothers tracked it down in the 1950s. How the tractor escaped the scrap drives of World War Two is unknown.

Rumely was a builder of farm machinery, but best known for the Rumely Oil-Pull line of tractors. Over the course of the Rumely Company’s life, it accumulated other farm machinery companies including the Advance Thresher and Gaar-Scot companies. After these acquisitions, the company became known as the Advance-Rumely Company. Advance –Rumely went on to acquire the Aultman-Taylor Company.

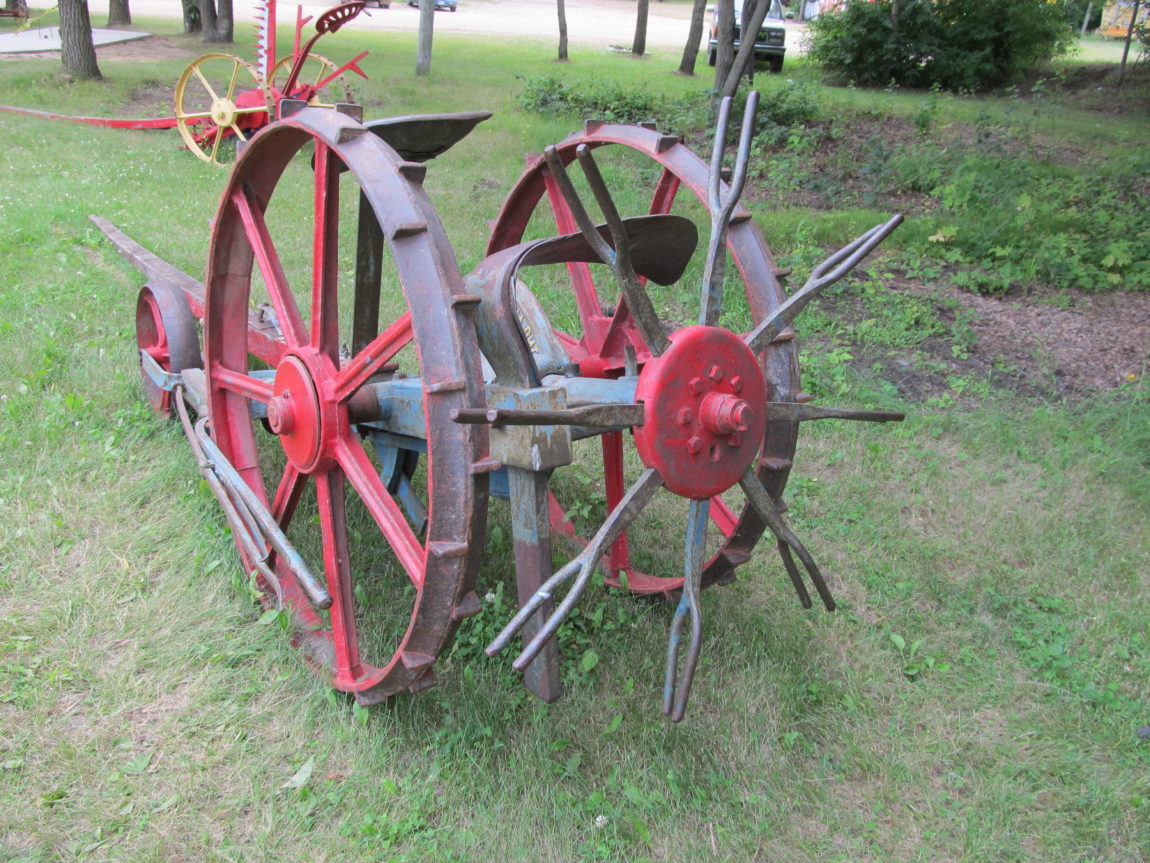

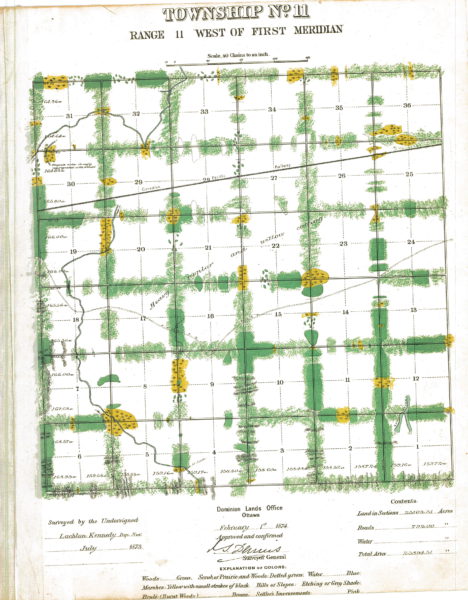

The Rumely Company originally got its start when Meinrad Rumely left Germany and joined his brother in LaPorte, Indiana to operate a foundry. By 1859, the brothers were making corn shellers and horse powered threshing machines. The brothers went on to produce steam engines and a variety of other farm machinery including clover hullers, plows, cutting boxes, corn shellers, corn shredders, silo fillers, water wagons, cream separators and motor trucks. Rumely had a reputation for building quality machinery.

Rumely built a number of models of the Oil-Pull starting with the “B” and progressing on to the “E”, “F”, “G”, “H” and “K”.

The “E” was the largest of the “Heavy Weight” Oil-Pull tractor. The design was rated at 30 horsepower at the drawbar and 60 horsepower on the belt. Model Es were equipped with a two cylinder engine and as with all Oil Pull tractors the cooling fluid was oil. Model Es were built from 1910 to 1923 with 3,235 being produced.

The great depression resulted in the Advance–Rumely Company encountering financial difficulties. Allis-Chalmers purchased the company, mainly for the dealer network that Rumely had built up. Allis kept the Rumely 6A tractor, an up to date design, in production as well as the Rumely combines but all other Rumely machinery was discontinued.