The Manitoba Agricultural Museum has three intact Stewart Sheaf Loaders in the collection. Given the machine was built with a steel frame made of square steel tubing and flat iron, materials which would have been very useful in other projects when the useful life of the machine had passed, the survival of three machines to be donated to the Museum indicates the Steward Sheaf Loader was sold in some numbers.

Of the three Stewarts in the collection, two were built by the Stewart company and the third one was built by the Acme Manufacturing company which purchased the design in the late 1920s and continued production of the loader after the Stewart company ceased production. The Acme in the Museum’s collection was donated by the Jordan Family of Altamonte, Manitoba.

The handling of sheaves in the field was a sufficiently large enough problem that a number of pieces of equipment were developed to address the problem. The Steward Sheaf Loader was one such machine and offered the ability to load sheaves on a wagon faster and with less physical labor.

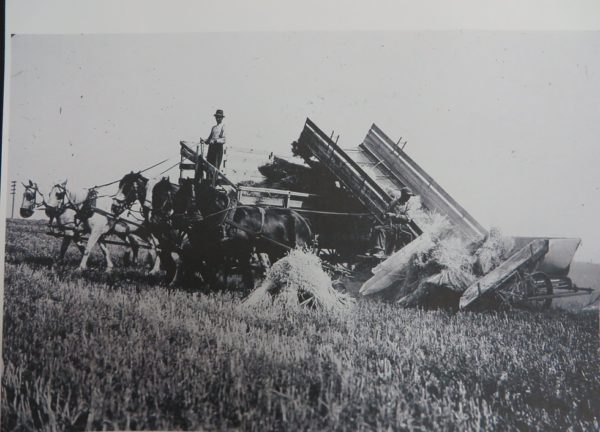

The Stewart Sheaf Loader is a simple machine consisting of a pickup which picked up stooks of sheaves and elevated the sheaves several feet in order to drop them onto a cross elevator equipped with a slatted chain which then took the sheaves higher up into the air and dropped them on to a sheaf wagon being driven along side the Sheaf Loader.

The machine was originally ground driven however late model loaders had the option of being PTO driven as, by the late 1920s, many tractors had the option of being fitted with PTOs. As stated earlier, the Stewards were built with a frame made out of square steel tubing and flat iron. One of the Stewards in the collection has a wooden deck on the pickup which indicates it is a fairly early machine. The other two have galvanized steel decks on the pickup. The decks of the elevators on all three machines were made out of galvanized steel sheeting as were the sides of the pickup. The sides of the elevators on all three machines are wooden boards on a steel frame.

The machines were driven beside a row of stooks with the stooks then being picked up and elevated into sheaf wagons, taken to the thresher & threshed. The loader cut in half the number of men and teams needed by the outfit which was a big saving to the farmer and more than likely a welcome relief to the farmer’s wife and daughters who had to prepare meals for a hungry threshing crew.

The sheaf wagons could be any one of a variety of designs, a basket rack with built up sides, a barge type body or just a normal rack with ends. More than likely, a basket rack was preferred. The right side of the basket was higher than the left side in an effort to maximize capacity and reduce the chances of sheafs being thrown over the wagon. When pitching the sheaves into a thresher, the wagon was parked so the low side was beside the threshing machine’s feeder in order to reduce the labor involved in pitching.

It has been suggested to the Museum that many veteran sheaf pitchers who loaded sheaf wagons by hand did so in a pattern so that the pitcher knew where to stand when pitching sheafs into the thresher and not be attempting to pitch a sheaf that he was standing on. Obviously with a wagon loaded by a Steward, the sheafs were loaded helter skelter onto the wagon so the pitcher could have more work unloading the wagon.

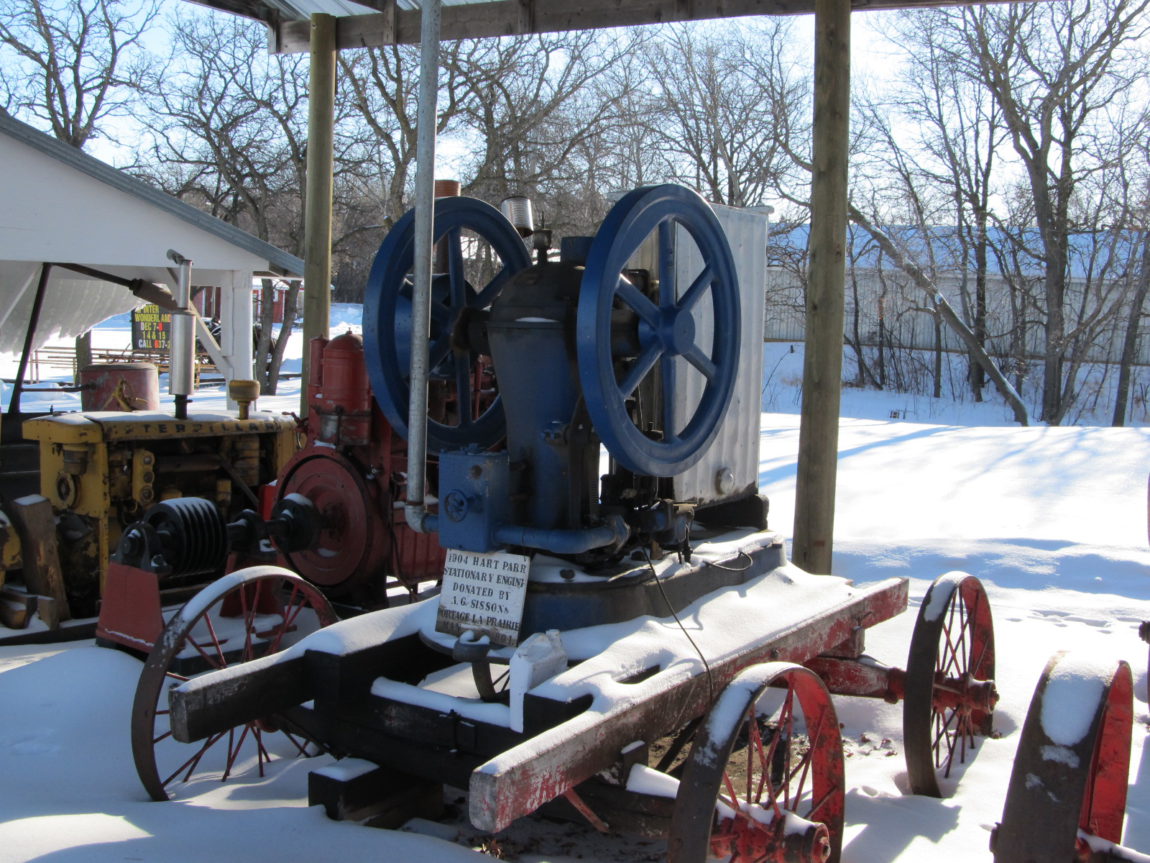

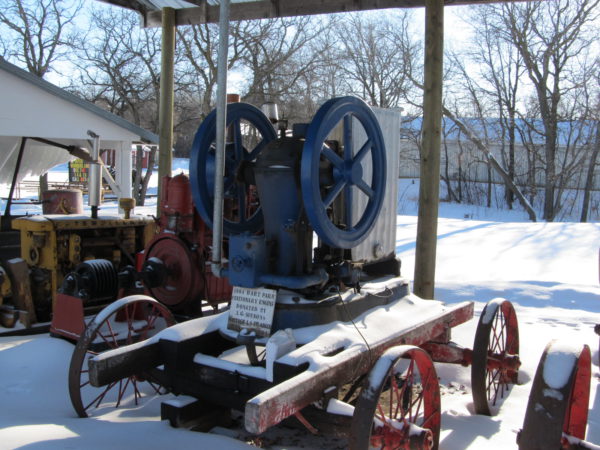

There are ads showing other pieces of labor saving sheaf handling equipment such as end dump sheaf wagons. There were three companies advertising end dump wagons in the 1913 Canadian Thresherman and Farmer magazine; Perfection, Maytag and Hart. As well, there is an ad for a threshing machine feeder with an feeder apron that dropped onto the ground. If a farmer had a loader, end dump wagons and a dropped feeder apron then handling sheaves would have reduced significantly the physical labor of handling sheafs.

The Steward Sheaf Loader Company Ltd. owned an office and plant at 470 Martin Avenue in Winnipeg and appears to have operated between 1910 and sometime in the mid to late 1920s. Most of the company’s output was sold in Western Canada and it appears sheaf loaders were not used to any great extent in the US.

The Steward Sheaf Loader originated with the Stewart Family of Molesworth, Ontario where the family was involved in farming. The eldest brother, Peter “M” Stewart, moved west in 1879, a common story with Ontario farming families as land was cheaper to obtain in the West. He went farming in the Neepawa, Manitoba area. Dave Albert, Robert C. and John F. Stewart , all of whom were very fond of “tinkering” with machinery, remained in Molesworth, Ontario. According to Stewart Family history, Dave Albert and Robert C., were the inventive ones, while John F. did the farm-work and was an excellent blacksmith that brought the ideas to reality. Jennie Stewart, a sister, should also get credit in the Steward Sheaf Loader story as she was very good with numbers and aided in the design calculations that helped produce the loader.

The Stewart brothers remaining in Ontario came up with the idea of a sheaf loader from their experience in threshing grain and thinking about how the amount of hand work could be cut down. Patents on the machine were taken out in 1902 and 1905. A prototype sheaf loader was built in their workshop in Molesworth then crated and shipped by rail in 1905 to Neepawa, Manitoba for trial on the farm of their brother Peter “M”. The first trial, however, was not a success, owing to the heaviness of the oat crop. Family history also indicates there were problems stemming from the fact the stooks of oat sheaves had stood in the field for a long time. Perhaps the oat plants had started growing from the root and a heavy growth of new oats was impeding the pickup? But whatever the cause the Stewart brothers decided the loader was not heavy enough to do the job. So, the loader was re-crated and shipped back to Molesworth. Here, the brothers set about rebuilding it, adding larger gears & a larger “bull wheel”. This time, it did work. The machine was then shown at the Winnipeg Exhibition in Winnipeg, about 1910. The Stewart Sheaf Loader went into production at 470 Martin Avenue, Elmwood, a suburb of Winnipeg, where the Stewart Brothers had obtained a manufacturing facility.

The Stewart Sheaf Loader was used all over the western prairies and cost about $400.00 to buy. David Albert took out another patent on improvements to the sheaf loader in Winnipeg in 1912 and John F. took out a duplicate one in Ontario in 1912. These patients related to a change in how the elevator was driven. Originally, the elevator’s slatted chain was driven by sprockets at the bottom of the elevator on the right side of the machine (when you are standing at the back of the machine). The Stewards determined that it was better that the slatted chain be powered by sprockets at the top of the elevator as the slatted chain, sheaves and all,was then being pulled to the top of the elevator. The old arrangement saw the chain being pulled all the way around the elevator which required more power and also resulted in slats being broken on the chain for some reason. Testimonials from farmers who converted Steward Sheaf loaders to the new drive arrangement indicate one less horse was required with the remaining horses remaining in better shape and the problem with breaking slats disappearing.

The Stewart brothers probably got into the “inventing” business because they liked working with machines and were very good at it. The Sheaf Loader was only one of many things they designed and patented over the years. The rights to one of these (the straw cutter on the threshing machine) was later sold to the “George White Company”, that built threshers. David Albert Stewart eventually returned to Molesworth and all 3 brothers are buried there.

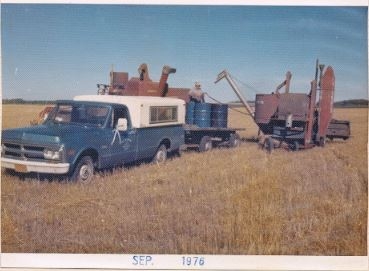

The Stewart Sheaf Loaders was built commercially from 1910 to some time in the 1920s. It appears the Acme Manufacturing Company then purchased the Stewart Sheaf Loader design and built further machines. With combines coming into use on the Prairies by the mid 1920s, the market for sheaf loaders slowly dried up. Oddly enough, sheaf loaders seem to be mainly a Canadian development and few were sold into the US. It is not known when the Acme Company discontinued the production of sheaf loaders.

A fellow by the name of Nelson Jackson used a Stewart Sheaf Loader on a Neepawa area farm in 1913 and decided he could improve on the machine by combining the rack and sheaf loader into one machine. He moved to Brandon and began manufacturing his machine there. The Jackson Sheaf Loader featured an elevator that directly picked up the sheafs, elevated them and dumped them into a carrier at the back of the machine. When the carrier was full the machine was taken over to the thresher and the sheaf dumped beside the feeder. While these sheafs were being forked into the thresher, the Jackson loader returned to the field for another load of sheafs. The downfall of the Jackson appears to have been the weight of the machine, particularly when loaded with sheafs. Another problem would be breakdowns. With the Steward if the loader broke down, the farmer could revert to forking sheafs into the sheaf wagons and so limp along until repairs were made. If a Jackson broke down, then everything came to a halt until repairs were made. Sometime around the end of World War One, Jackson moved his company to Saskatoon and resumed manufacturing the loaders there. However business soon dried up and the company pursued other ideas.