From our 2015 Reunion parade:

From our 2015 Reunion parade:

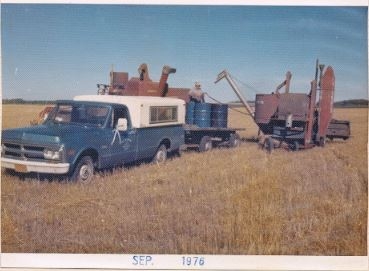

Before Cockshutt built its well known self propelled combines, Cockshutt built a couple of pull type combines models. The Number 6 was in production in 1939 and 1940 and the Number 7 replaced the 6 in 1941.

The Number 7 featured a 38 inch cylinder with a 6 foot or 8 foot cutting table width. The machine was available either with power take off drive or an auxiliary engine drive. The auxiliary engine option featured a 4 cylinder Hercules IXB-3 gasoline engine. The grain tank held 35 bushels. A re-cleaner has been fitted to this machine.

Oddly for a pull type combine the table is on the right side of the machine. Standard practice was for a left hand side table.

The machine was put into production in 1941 to replace the Cockshutt Number 6 combine and may have remained in production until 1954 when the Cockshutt Model 422 pull type combine was introduced.

Canadian farm implement manufacturers continued to produce farm machinery and parts through the Second World World War but at a much reduced level of production. It was important for Canada to fill Britain’s need for food. To complicate matters, much farm labor had enlisted in Canada’s armed forces leading to farm labor shortages. So the Canadian government decided that steel, other materials and factory space had to be allocated to farm machinery production as this machinery was needed to replace the lost labor. The government allocated materials to specific types of machines on a complicated formula based on 1940 production, demand for farm products and the amount of labor saved by a particular machine. Overall production was set at about 25% of 1940 production of complete machines with parts production at 150% of 1940 production. The Cockshutt annual report for 1942 listed the shipment of 500 Number 7 combines in the fall of 1942.

The MAM collection includes a Cockshutt Number 7 pull type combine however this combine is painted in Co-op colors.

Cockshutt wanted to increase sales in 1945 which meant it had to get into the US market. Cockshutt and the US based National Farm Machinery Co-operative (NFMC) came to an agreement where Cockshutt implements were sold through NFMC outlets across 11 states. Frost and Wood, a subsidiary of Cockshutt which made haying and harvesting equipment .was also included in this deal. The deal with NFMC allowed Cockshutt into 11 states where Cockshutt had no previous presence and all at a low cost.

However to get the deal with NFMC, Cockshutt also had to agree to supply equipment to Canadian Co-operative Implements Limited (CCIL). Cockshutt was not in favor of supplying equipment to CCIL as CCIL would be in competition for sales of equipment with Cockshutt operations in Western Canada. However the NFMC was adamant that CCIL was to be included. The deciding factor was that both Co-ops agreed to take a large amount of equipment and would pay for this equipment in advance. As Cockshutt at the time was in the process of developing its own tractor line and expanding its combine line, this money was needed by Cockshutt and so Cockshutt agreed to supply NFMC and CCIL. Cockshutt painted the equipment supplied to both co-ops in each of the co-ops color schemes. The orange used by CCIL was different in shade from the orange used by NFMC.

Along with moldboard plows, the Cockshutt Plow Company Limited also built disc plows. Disc plows are suitable for the very sticky soils found in many areas. These soils pose problems for moldboard plows. Cockshutt built both horse drawn disc plows and tractor drawn disc plows which ranged in size from one disc to five discs. Along with Cockshutt built plows, Cockshutt also sold the Angell Disc Plow from the Ohio Cultivator Company which came in 6 ft, 8 ft and 10 ft sizes with 20 inch discs. Selling the Angell allowed Cockshutt to offer a more complete line of tillage equipment with a minimum investment. From the Ohio Cultivator Company point of view, an arrangement with Cockshutt increased sales in Canada, an area where the company had no presence, and all at a low cost to Ohio.

However, in 1931, Cockshutt took the Angell concept and made a huge leap forward. Cockshutt designed their version of the Angell making a number of improvements along with one important innovation, that of mounting a seed box on the machine. This machine they called a tiller combine.

The Cockshutt Tiller Combine featured disc blades mounted 7 1/2 inches apart. The disc blades were 24 inches in diameter which was a smaller disc than the 30 blades featured on Cockshutt disc plows. All blades were mounted on a single shaft, raised and lowered by a power lift. The shaft was supported on ball bearings, so the entire assembly (shaft and blades) rotated. The depth of penetration of the soil by the blades could be adjusted. When seeding, the seed box dropped the seed down tubes which ran immediately in front of the shaft, and close to the back of each blade. Each blade had its own tube. As the seed was dropped, the blade following behind threw dirt over the seed.

For 1931, the Cockshutt Tiller Combine was a revolutionary concept as the machine was a combined plow, light disc and seeder. Only one field operation was necessary, that of seeding the land in the spring. Fall plowing was not necessary, which saved time, money and even more importantly, conserved moisture and reduced soil erosion as the stubble was left on the field to trap snow and slow down the wind at the surface of the soil. When seeding, the combine tiller left a rough surface which aided in reducing wind erosion. The tiller combine did not pulverize the soil, which also aided in reducing soil erosion. Given the drought conditions of the 1930s, the Cockshutt Tiller Combine was the right machine at the right time.

The Cockshutt Tiller Combine was available in 3.5 ft and 4 ft sizes, suitable for horse traction. The Tiller Combine was also produced in 6 ft, 8 ft and 10 ft sizes suitable for various sizes of tractors.

In 1931, Cockshutt sold 100 units. While this number is small, one must remember the conditions experienced in 1931 of a widespread and serious drought, a collapse in farm prices and a sever economic recession. 100 units in this context was a significant achievement which indicates the concept behind the Tiller Combine was a solid one, that farmers saw value in. Further proof that the concept was a good one was the copying of the Cockshutt Tiller Combine by other farm equipment manufacturers in the years after 1931.

The MAM collection includes several Cockshutt Tiller Combines including one set up for horse operation with an operator’s seat on the machine. The collection also includes a Cockshutt Tiller Combine painted Canadian Co-operative Implements Limited Orange and sold through CCIL. This machine was built sometime after mid-1945.

Cockshutt wanted to increase sales in 1945, which meant it had to get into the US market. Cockshutt and the US-based National Farm Machinery Co-operative (NFMC) came to an agreement where Cockshutt implements were sold through NFMC outlets across 11 states. Frost and Woods (a subsidiary of Cockshutt) which made haying and harvesting equipment, was also included in this deal. The deal with NFMC allowed Cockshutt into 11 states where Cockshutt had no previous presence, and all at a low cost.

However, to get the deal with NFMC, Cockshutt also had to agree to supply equipment to Canadian Co-operative Implements Limited (CCIL). Cockshutt was not in favor of supplying equipment to CCIL, as CCIL would be in competition for sales of equipment with Cockshutt operations in Western Canada. However, the NFMC was adamant that CCIL was to be included. The deciding factor was that both Co-ops agreed to take a large amount of equipment and would pay for this equipment in advance. As Cockshutt at the time was in the process of developing its own tractor line and expanding its combine line, this money was needed by Cockshutt. And so Cockshutt agreed to supply NFMC and CCIL. Cockshutt painted the equipment supplied to both co-ops in each of the co-op’s color schemes. The orange used by CCIL was different in shade than the orange used by NFMC.

Cockshutt entered combine production in the late 1930s with the introduction of the Number 6 pull type combine.

Well before the Second World War wound down to an end, Cockshutt began planning for the post war period. Cockshutt recognized that the reduced agricultural equipment manufacture resulting from the war along with increased agricultural production would result in the existing stock of farm equipment being worn out by the end of the war. As well farmers would have built up significant bank balances due to decent prices and demand for agricultural products. So there would be good demand after the war for modern farm machinery.

In addition, Cockshutt had modernized their manufacturing plants to manufacture war material for the government. In many cases the government had actively assisted manufacturers, including Cockshutt, to obtain modern manufacturing equipment and develop the needed technical skills to operate this equipment. As well war demands had also resulted in manufacturers being able to increase their engineering staff. Cockshutt as a result had greatly increased capabilities as a company.

One of the first wave of new products for the post war period was the development of a self-propelled combine. The Models SP109 and SP110 were in farmers’ fields in the fall of 1944 and were well received. Cockshutt developed the self-propelled combine line further after the war and introduced further models offering further developments such as hydraulically controlled tables, power steering and variable sheave traction drive.

The MAM collection contains a Cockshutt 428 self-propelled combine. The 428 was in production between 1956 and 1962. The standard 428 come with a 12 foot header however 10 or 15 food headers were offered as options. Other standard equipment included a Chrysler flat head 6 cylinder industrial engine offering 76 horsepower and a Cockshutt Drive-O-Matic traction drive which was a four speed transmission coupled to a variable sheave drive. The variable sheave drive was hydraulically controlled off a foot pedal on the operator’s platform. This combination offered ground speeds varying from 5/8 to 9 MPH. The table was hydraulically raised and lowered.

The cylinder had 8 rasp bars and was 311/4 inches long and 21 7/8 inches in diameter. The speed of the cylinder could be varied from 727 rpm to 1178 rpm. The separation area was 32 inches wide and 117 inches long.

Accessories included a retractable finger auger on the table, lights, a pickup reel with 4 or 6 inch tooth spacing, ScourKleen auxiliary recleaner, slow speed cylinder sprockets, straw spreader and hour meter.

The Cockshutt Model 427 was essentially the same machine only a smaller engine was used which offered only 72 horsepower.

While Cockshutt had an extensive line of tillage equipment and of harvest equipment, Cockshutt lacked a tractor to fill out is line up of farm machinery. With other machinery companies offering a complete line of machinery, Cockshutt was at a disadvantage. Farmers had a reason to visit another farm machinery dealer and while there the farmer could be “converted” to another make of machinery. Cockshutt noticed that its sales were slowly declining with farmers turning to other farm machinery companies. However Cockshutt also realized:

To fill out the line with a tractor, in 1928 Cockshutt began selling Allis Chalmers 20-35 tractor. In 1929 the Allis Chalmers Model U began to be sold by Cockshutt. However the Model U was plagued by engine problems which were severe enough that Allis Chalmers arranged for a short block engine exchange beginning in 1931. A new engine was introduced into the Model U in 1934.Cockshutt is suspected of being unhappy with the engine problems experienced by the Allis Chalmers tractors. Cockshutt signed an agreement in 1935 with the Oliver Company to market the Hart Parr line of tractors in Canada. Oliver had more production capacity than sales for Hart Parr tractors and so Oliver was interested in a larger share of Canadian tractor sales. And Cockshutt needed a good tractor line and the Canadian farmers were aware of the Hart Parr line of tractors.The first Hart Parr tractors sold by Cockshutt had the name Cockshutt cast into the radiator tank with the words Hart Parr in smaller letters cast below. The tractors came painted in a dark green with red wheels. Cockshutt sold the Model 60, 70 and 80 tractors produced by Oliver.The Oliver Model 8 tractor appeared in 1937 and stayed in production until 1948. The 80 was available in both standard tread and row crop configuration. A Buda-Lanova diesel engine was an option that could be ordered on the Oliver 80. However the most common engine in an Oliver 80 was an internal combustion engine built by Waukesha for Oliver. This engine could either be set up for kerosene or gasoline fuel operation.

The Manitoba Agricultural Museum has a late model Sunshine Waterloo combine in the collection.

The Sunshine combine was a design of the H.V. McKay Company of Melbourne, Australia with the first one built by McKay in 1924. While we would call this machine a combine, the Australians call it a stripper header not because one needed to be naked to operate it but rather because the machine was equipped with a comb type header to straight cut grain by cutting the stalk immediately below the head so only the heads and a minimal volume of stalks were taken into the cylinder to be threshed. In other words, only the head was stripped off the stalk during harvest. This form of operation was successful in Australia as the growing seasons are quite long and there is no winter with snow at the end of the season. In many areas of Australia as well the growing season is timed so as the harvest begins with the onset of summer when the weather becomes hotter and drier. The crop then can remain out in the field until perfectly dry.

Stripper type headers for combines have been experimented with in Canada over the years but have not found favor on the Prairies. One reason is that straw is needed in many areas to bed cattle during the winter. The operation of a stripper header would result in no straw being readily available for baling. Another reason would be that many areas of the Prairies are wetter than Australia and more straw is produced. If this straw was left standing in the field it would cause issues with further field operations. So farmers are inclined to cut it down and chop it up with the combine. Canadians could also be victims of the “not invented here” syndrome however.

The first Sunshine Auto Headers used a Fordson engine. In 1926 McKay switched to a Wisconsin 4 cylinder in-line water-cooled engine. The model WA, WT and WB Auto Headers had a 30 HP engine and 2 forward (3 mph, and 2 mph and 1 reverse gear 1.4 mph. The width of cut was 12 feet. In 1937 the improved KA and KT headers were produced with a 36 HP engine, a 3 speed gear box and a forward/reverse gear and a hand over-centre clutch. The platform raising and lowering were power operated and the cutting width was 12 or 14 feet. All models featured a reversed tricycle type of wheel arrangement with one-wheel drive. A pinion on the inside of the gear-box drove an internal ring gear on the 54 inch diameter drive wheel at the front of the machine on the right side. On the left front side was a 54 inch diameter un-powered wheel. There was a lone 30 inch wheel at the back of the bagging platform that did the steering. All wheels were steel. The engine was immediately beside the drivers seat. With the engine so close perhaps many operators did remove their clothes in order become more comfortable when operating the machine.

In 1929 McKay and Massey-Harris along with the Waterloo Manufacturing Co. incorporated the Sunshine-Waterloo Company Ltd. with the intent of adapting McKay’s self-propelled combine design for the North American and Argentinean market. In 1930, the newly formed company built a 285,000 sq. ft. plant in Waterloo, Ontario. In exchange McKay was granted the exclusive Australian distribution of Massey-Harris farm equipment.

Although set up to produce mainly farm equipment, in order to survive the tough economic times of the thirties, the new company manufactured a multitude of products, including baby carriages, bicycles, tricycles roller skates and automotive stampings for cars. Waterloo Manufacturing withdrew from the joint venture in 1934.

During World War Two the Sunshine Waterloo Co. was a major producer for the war effort as a result of being converted to war production in 1939. During the war security was high at the plant due to the fact that it produced tank, airplane and truck parts, as well as ammunition, land mines, and various bombs.

After the war the company resumed production of bicycles and began producing office products, stoves, shelving and lockers. The Sunshine combine was rather dated by this time and does not appear to have been put back into production. In 1955 the McKay family sold their holdings to Massey Ferguson. In 1961, Sunshine Waterloo became the Sunshine Office Equipment Company. The company wrapped up operations in 1978.

Hugh Victor McKay was an early pioneer in the combine field. Australian farm machinery in the late 1800s was quite different than what was developed in North America. With no need to harvest straw the Australians had developed a horse drawn stripper type header. This simple machine just cut off the heads and dumped them into a box. This material was then taken to a hand powered or horse sweep threshing cylinder which threshed these heads with the grain and chaff then going on to a separate machine, the winnower, which cleaned the grain. McKay hated cranking the winnower apparently and decided to build a machine that would do all these seperate operations in one machine. After collecting a number of old or junk machines including a reaper, binder, winnower and a stripper header plus assembling a set of blacksmith tools McKay and one of his brothers set to work. By 1884 they had a prototype which managed to harvest two acres of wheat. The machine was named the “Sunshine” harvester.

The Sunshine Harvester’s benefits were immediately obvious and McKay enjoyed good sales success. By 1920. H.V. McKay owned the largest farm implement factory in the Southern Hemisphere and had significant sales outside Australia. At its peak, the enterprise employed nearly 3,000 workers.

Massey-Harris did a lot of business selling grain binders but did not have a combine. In 1900 Massey-Harris joined with H.V. McKay and wasted no time getting into the Australian market with their stripper/thresher. This machine stripped the grain heads off and sent them directly into the threshing cylinder and on to the cleaning shoe. The Australians were quick to adopt the bulk-bin concept. The bin could dump directly into a waiting wagon or could drop the grain into sacks for hauling away. Sacking required two people and quickly fell out of favor.

Hart Massey had begun experiments with a stripper header in the 1880s. A stripper header was a machine that cut the heads off standing grain and the heads then were conveyed into a thresher – cleaner which threshed the kernels out of the head and discarded any chaff , awns and other debris. Stripper Headers really only worked well in areas where grain could dry while standing. Western Canada was not the place for this technology given the long time to maturity of the wheat varieties in use in the 1880s, E.G. Red Fife. An early winter could result in snow falling on the crop flattening it. A stripper header could not cope with this condition. Stripper headers were commonly used in areas such as Australia, California and Argentina. However Massey persisted with the stripper header even after the amalgamation that saw Massey Harris formed. Massey Harris built and shipped 350 stripper headers in 1901.

Massey Harris in 1906 began work on a travelling combined harvester thresher and hired two Australian engineers. These engineers split the year between Australia and Canada working on designs. By 1909, they had developed a machine that cut a standing crop, conveyed the stalks to a threshing cylinder which threshed the material and dumped it out onto straw walkers under which were sieves through which air was blown. The air flow cleaned the chaff and debris from the grain, when properly adjusted. This machine featured a ground wheel drive and a 9 foot cut. Operators on the machine had to bag grain as it came through the sieves.

This machine was introduced to the market as the Massey Harris Number 1 in 1910. The machine was further improved with new models coming on to the market. In 1922 the Massey Harris Number 5 was introduced. The Model 5 was the first Massey Harris combine to feature an engine drive. All previous Massey Harris combines had featured ground wheel drive. The Number 5 could be drawn by either a tractor or horses.

With the new Model 20 performing well with big acreage growers, including export demand from countries such as the USA and Argentina, Tom Carroll and the combine design team at MH quickly set to work designing a smaller SP combine two-thirds the size of the No.20. The aim was to develop a new smaller, lighter and more affordable self-propelled combine that would sell in large numbers to smaller farms.

The resulting machine had a 12-foot cut and was built much lower with the engine underneath. The table used draper canvases. These did a nice job of feeding the grain heads into the feeder house. It was priced within range of the”average” farmer.

Sales of the Model 20 totaled 925 machines over two years, but when the new MH-21 combine arrived in 1941, it created a huge demand with annual production peaking at 10,000 plus in 1949. However in the war years of 1939 to 1945 steel supplies limited production along with shortages of components such as the Chrysler six cylinder engines.

During the Second World War Massey-Harris and the Model 21, pioneered the “Harvesting Brigade”. The company gained permission to build a fleet of 500 Model 21s and sell them to custom operators who were to work north from the southern states of the US Great Plains area and in doing so follow the ripening harvest north. Materials such as steel, engines and other components were rationed during the war in order to ensure allied military forces had sufficient supplies. Massey Harris had to convince the authorities that 500 Model 21s were sufficiently valuable to the Allies cause that materials could be allocated to build them along with the factory space as Massey Harris plants had been converted to build a variety of military equipment. Massey Harris made their case for the materials and plant space by pointing out the machines would save labor, release tractors for other uses and tractors were in short supply at the time plus the machines would reduce harvest losses due to tramping grain when opening up fields with pull type combines or to broken sheaves if the field were being harvested by binder and threshing machine.

The plan worked as the machines harvested more than a million acres in one year and freed up an estimated 1,000 tractors for other work while doing so. Massey Harris worked hard to ensure the program was a success by positioning spare parts along the route north through the Great Plains.

Even more importantly for Massey Harris, the Harvest Brigade had given a large number of farmers a very positive impression of Massey Harris self propelled combines. When the war ended, and they were able to switch back to normal production, demand for Massey Harris combines was immediate.

After the war Massey Harris introduced the Massey Harris Model 21A which used an auger on the table instead of draper canvases to feed grain into the feeder house. However the Model 21A auger did not feature disappearing fingers.

With the MH-20 and MH-21 combines Massey-Harris achieved an important breakthrough in grain harvesting, which other combine manufacturers were forced to follow.

Tom Carroll’s role in the development of the Massey Harris combines was not forgotten and he was awarded a Gold Medal in 1958 by the American Society of Agricultural Engineers to recognize his contribution to combine harvester development. Along with the first successful self propelled combine, Tom Carroll helped introduce to the farm machinery business mechanical improvements such as welding, roller chain, oil bath gear sets, ball bearings and detachable tables which made combines easier to transport.

Beamish Family Massey Harris Model 21 Combine

The Museum has two Model 21s in the collection and both operate.

The Beamish Family donated this Model 21 to the Museum in 1979. The machine was purchased new in 1947 by Douglas and Richard (Dick) Beamish. When new the machine was fitted with a canvas draper pickup table. The machine was joined in handling the Beamish harvest by a Massey Super 27 in the late 1950s. In 1967, the pickup table was changed to the auger type making the machine equivalent to a Model 21A. The Model 21 and the Super 27 soldered onwards but with the finish of the 1979 harvest they were retired. The Model 21 was donated to the Museum at that time.

The other Model 21 in the collection is still fitted with the canvas draper pickup table and is an earlier machine than the Beamish Model 21 as it is fitted with galvanized sheet metal. Originally the Model 21s were built with galvanized sheet metal and later production used painted sheet metal. Originally the Beamish machine sported a red paint job but time has turned the sheet metal to a patina of brown and surface rust.

The advent of plowing with steam engines posed significant problems as the first plows used behind an engine were adopted from animal traction plows. As these plows at best could only feature three bottoms and usually less than that, most engines had the power to draw multiple units behind it. How to hook all these units together and keep them properly trailing behind the engine was a problem. As well, the engines being more powerful often caused the horse traction plow frames to fail. The Cockshutt Plow Company recognized the problems and set out to design plows specifically for mechanized traction. In 1903, Cockshutt introduced heavy duty three and four bottom plows suitable for mechanical traction. If a farmer needed a plow larger than three or four bottoms, the farmer could hook two or three of the Cockshutt units together by using what Cockshutt called a “jockey rod”. However an operator was needed on each unit to work the levers to raise and lower the bottoms.

Cockshutt then introduced another new plow designed for mechanical traction, the Engine Gang Plow. This design featured one frame and required only one operator. There were three basic sizes ranging from 6 bottoms to 12 bottoms. The basic frame was constructed out of heavy angle iron in a triangular shape. All sizes used identical moldboard assemblies attached side by side across the angled rear of the frame. Each moldboard assembly was a plow in itself and was hinged to the frame. Each assembly had its own depth gauge wheel, allowing individual assemblies to float and follow the contour of the ground. As these assemblies were identical, if one was damaged the plow man could easily remove two hinge pins to remove the damaged assembly, take a complete assembly off the outward end of the plow to replace the damaged assembly and continue plowing. With repairs and parts some distance and time away in the Pioneer era, this was a useful feature.

Other makes of plow used one depth gauge wheel and lift lever to control two bottoms so requiring more physical strength to lift the section. This arrangement also caused problems in making the plow work level.

Cockshutt Engine Gang plows were very common on the prairies, not only as this design offered advantages over other makes of plows but also as the tariff structure of the time resulted in heavy taxes being imposed upon imported farm machinery. This gave a price advantage to Canadian built machinery. Cockshutt claimed to have sold 800 Engine Gang plows in a Cockshutt advertisement in the April, 1910 edition of the Canadian Thresherman and Farmer magazine

The Museum has a 12 bottom Cockshutt Engine Gang plow in the collection. This plow is fitted with wheat land bottoms not breaker bottoms. Breaker bottoms have a longer moldboard which was found useful in turning over sod.

James Cockshutt started the Brantford Plow Works in 1877 and built a number of different models of plows along with other products. However as Western Canada opened up to homesteaders in the 1880s, James Cockshutt found that plows designed for Eastern Canada were not completely suitable for the prairies with its blanket of tough wild grasses possessing a thick root mat. So Cockshutt designed a single bottom riding plow that possessed a stronger frame than eastern plows plus a moldboard with curvatures designed for prairie sod.

The best way for a plow to cut into sod or dirt while, at the same time, lifting and turning the material over through 90 degrees is with a moldboard that possesses a spiral curve across the face of the moldboard. The properly curved moldboard would result in reduced draft or tractive force necessary to move the plow and so result in economical plowing. To complicate matters a different spiral curve is required for the moldboard to efficiently cope with the different soil types, depth worked and working speeds encountered plus produce the appearance of the plowed field that the plow man desires. Differently curved moldboards were then needed for clay, sand, sod, corn and wheat stubble, the slow moving breaking plow and so on.

From the day of introduction the JGC riding plow was a success in Western Canada and was in the Cockshutt catalogue from 1884 to 1931. Only limited changes were made during this time such as using built up spoke wheels instead of cast wheels and a steel pan seat instead of a cast iron seat.

The Museum has a number of JGC riding plows in the collection including the early plow with cast wheels and a cast iron seat that is seen on this page. This plow was donated to the Museum in the mid 1950s by L. Smith of Brandon. Other JGC plows in the collection have pressed metal seats and / or different wheels.

Soon after the JGC was designed, James Cockshutt passed away due to tuberculosis, a very common illness at the time and one for which no treatment existed at the time, other than retiring to a dry climate. As the Cockshutt family had been aware of James illness, the Brantford Plow Works was reorganized into the Cockshutt Plow Company and one of James brothers took the helm of the company before James passed on. Cockshutt went on to build a large number of plow models, as many as 130 as well as a number of other tillage tools. Cockshutt began building swathers, tractors and combines after World War 2. Cockshutt branched out into other products such as wagons and truck bodies as well. It is interesting to note Cockshutt during World War 2 built undercarriages for aircraft, aircraft engine exhaust components and the moulded plywood fuselages for Anson training aircraft and for Mosquito fighter bombers.