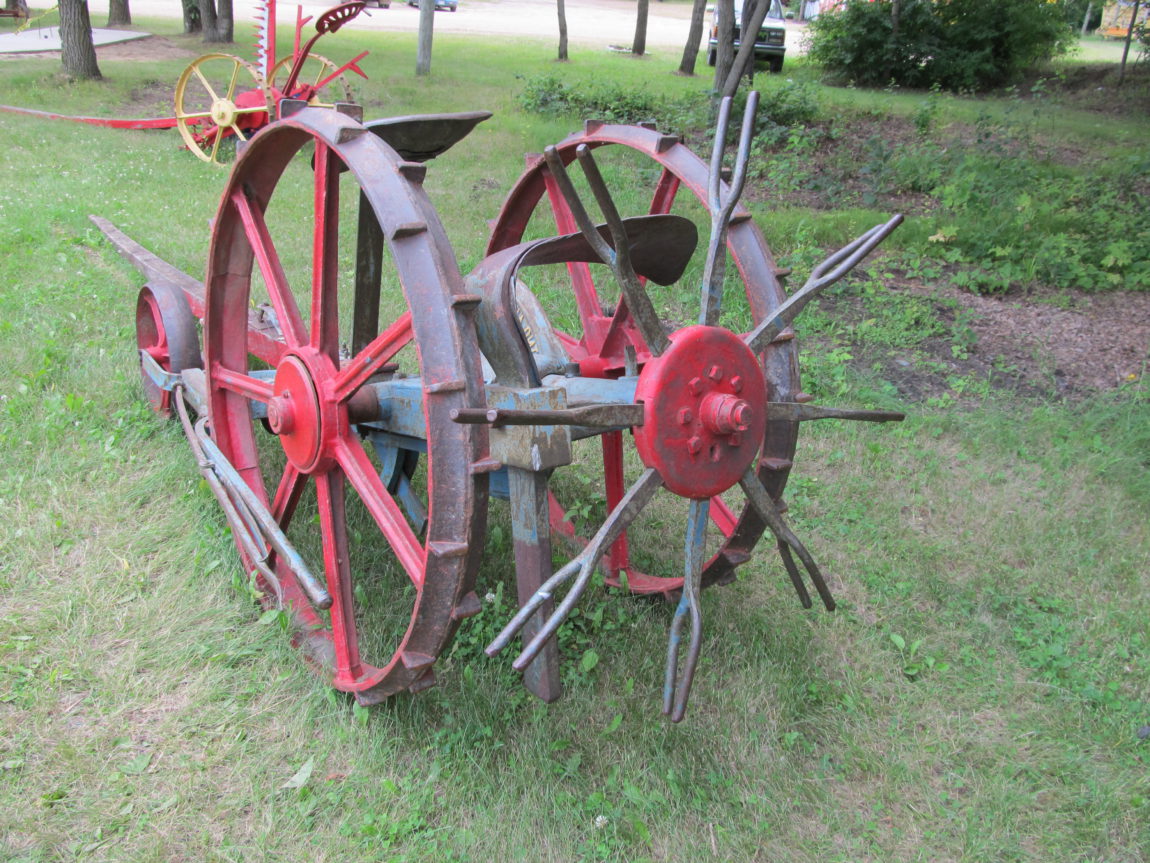

The Museum has three horse sweeps, one that has been rebuilt and is in use at the annual Threshermen’s Reunion and Stampede to drive either a baler or a hand-fed threshing machine. Two other sweeps are stored in the equipment yard in an incomplete condition. All three were donated in the late 1950s or early 1960s and came with the wooden components largely rotted away as they had been discarded outside many years previously.

About 1840, horse power sweeps were developed which could be used to drive machinery. Daniel Massey, an American who was then farming near Cobourg, Ontario imported a threshing machine and power sweep to drive it in 1845. Massey then started a machine shop and foundry and began to manufacture power sweeps around 1848. Massey went on to build other agricultural machinery and in so doing, laid the foundations of the Massey family involvement in agricultural machinery manufacture.

Horse sweeps were built in a variety of sizes from one-horse to eight-horse models. There were even models built which featured a built-in grain grinder or a stationary baler.

About 1875, Manitoba saw its first power sweep which was used to drive a threshing machine. Sweeps spread west with a power sweep and threshing machine being taken to Battleford, North West Territories (now Saskatchewan) as early as 1878.

The simplest description of a horse power sweep is that it is a right-angle gear box that sits on the ground with one shaft pointing straight up. The other shaft was parallel with and close to the ground. On the shaft that pointed straight up was attached an arm or a number of arms to which horses were hitched. The shaft that was parallel to the ground was attached to a long shaft lying on the ground. This shaft was long enough that it cleared the ends of the arms. This shaft drove another right angle gear box with a belt pulley on the output shaft of this gear box. A flat belt could then drive a threshing machine, circular saw, grist mill or other belt driven machine. The horse power sweep at the Museum uses this arrangement.

Power sweeps had some drawbacks. They were clumsy to move and because the machine took up a fair amount of room were impossible to operate in a building. In the winter or during cold weather, it may have been useful to operate the sweep inside a building to keep the horses warm and avoid issues with snow and ice. Sweeps also suffered from a built-in problem. While the horse was pulling on the end of the beam, the beam as it revolved, was moving off the line of draft. Overall, treadmills were more efficient than sweeps on a per-horse basis.

Oddly enough, horses were usually the only animal considered fit to operate a sweep. Oxen were a popular farm traction animal because the beasts, while slow, were powerful and did not require as much care as a horse. Oxen were also capable of eating lower quality forage than a horse. A further benefit may have been that, when the oxen became worn out, they were more acceptable for the stew pot than horses. However, oxen were not typically used to power a sweep because they were thought to be susceptible to becoming dizzy from walking in a circle. As well as horse sweeps, dog sweeps were also made. Dogs could power washing machines, cream separators, and similar light-duty equipment.

Horse power sweeps were common in pioneer Manitoba up to the 1900s but rare by the end of the 1920s. Gas engines and gas tractors by that time offered more economical horsepower.

A four-horse sweep in the Museum has been rebuilt with new wood components. This sweep has been examined however there are no markings present as to who manufactured the machine. When the machine was donated to the Museum in the late 1950s, there was no one who had seen the machine in operation so there are details of operation that the Museum is missing.