The museum’s elevator was built in beside the CPR tracks in Austin in 1905 for the Western Canada Flour Mills Company. The Western Canada Flour Mills Company was active in flour milling in Manitoba and operated a “line” or chain of grain elevators from 1905 to the late 1930s when the company was liquidated. The company operated flour mills in Saint Boniface and Brandon. The company owned 96 elevators in 1920 but by 1938 the company had sold all its elevators including the Austin elevator. The Brandon mill was on the north side of the CPR tracks just west of 1st street. It was closed in 1932 and demolished by the end of the 1930s. The company changed its name to Purity Flour Mills Limited in 1945. Purity was sold to Maple Leaf Milling in 1951. The Saint Boniface flour mill was closed in 1981.

It was common in the pioneer era for flour mill companies to own a line of elevators in order to accumulate the wheat that the mills needed. Information systems as to grain quality and quantity in the country plus farm storage systems were not well developed in Pioneer Manitoba. Apparently flour millers found buying and holding high quality stocks worked better than depending on being able to accumulate wheat of sufficient quality when the mill needed it. Other well known millers which also owned lines of elevators were the Ogilvie Milling Company and the Lake of the Woods Milling Company.

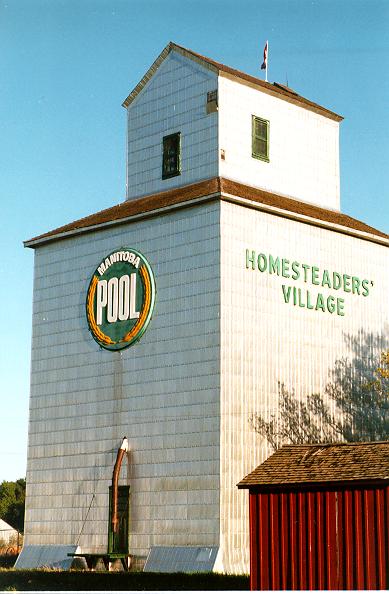

The elevator was built to a design that features a three-quarters-width cupola standing flush with the non-trackage side of the structure. Elevator design continued to evolve after 1905, growing taller and featuring cupolas that ran the full the width of the elevator structure. Designs previous to 1905 often featured cupolas that were ¼ width and centered on the top of the elevator. The cupola was necessary as the “leg,” a vertical spinning conveyor belt with cups attached and which carried grain to the top of the elevator, had to protrude above the bins so as to allow space for the hopper that caught the grain as it fell from the cups as they revolved over the top of the leg. From this hopper the grain fell into the “gerber” or distributor where it was directed by pipes or wooden chutes into the various bins. The small one-quarter and three-quarter width cupolas were cramped and added complexity in construction so elevator design standardized on full width cupolas.

The elevator was used for 33 years by the Western Canada Flour Company before being purchased by Manitoba Pool in 1938. Manitoba Pool used it as an annex on the main line at Austin until the fall of 1975 when it was emptied for the last time.

As the elevator had been last used as an annex, the elevators driveway / scale house had been removed as it was not needed. Annexes were simply grain storage buildings and were located beside and were fed from an elevator. An annex did not receive grain from either a truck or wagon, so there was no need for a driveway / scale house.

After moving to the museum, the driveway / scale house was rebuilt to its original appearance. As grain wagons were not large, the driveway was fairly narrow on early elevators. As larger trucks appeared, many elevators had to have the driveway / scale house widened to accommodate these trucks. Manitoba Pool also found and donated a Tiple-A device for lifting the front end of grain wagons so making emptying a wagon much easier with less shoveling needed. This device is combined with the scale.

The reason for the scale in the driveway was to determine the weight of grain being purchased from the farmer. The wagon would be weighed full and then weighed after emptying. The difference was the weight of the grain.

The wagons would dump grain into a pit under the scale. The pit floor was sloped so grain flowed to the lowest part of the pit where the bottom of the “leg” was installed. The leg lifted or “elevated” grain to the top of the elevator where the grain was dumped into a hopper feeding the “gerber” a device which could be set to direct the grain to one of the different bins that make up the body of the elevator. These bins have hopper bottoms. To load a boxcar, the bin with grain wanted for this shipment is selected, the bin emptied into the pit where it is elevated back to the top of the elevator and instead of being dumped into a storage bin, the gerber is set to direct the grain to the load out scale bin. As rail cars should not be overloaded, it was necessary to weigh the grain loaded into the car. From the load out scale bin the grain is dropped onto a scale, weighed and then dropped back into the pit where it is again elevated to the top of the elevator and then is directed into a pipe which takes the grain outside of the elevator. A flexible pipe is attached to the end of this pipe and inserted into the railcar. As grain is coming down, this flexible pipe can be shifted around to spread the grain out in the car.

While the above procedure sounds complicated, it was considerably faster and involved considerably less manual labour than the grain systems that the grain elevator replaced, the flat warehouse and the grain loading platform. A flat warehouse was simply a track-side warehouse where the farmer or a broker who purchased from a farmer stored grain in bags. When the grain was to be shipped, the bags were wheeled out beside the car and the grain bags emptied over the grain door into the car. A grain loading platform was loading dock where a grain wagon could be driven alongside the boxcar and the grain loaded into the car over the grain door. A shovel was not used but rather a grain scoup, a U-shaped piece of metal closed at one end and metal U-shapes for handles directly fixed to it. The museum in its early days had volunteers who had actually loaded cars using flat warehouses and loading platforms. They could attest that these methods were hard work.