This is a brief history of the formation of a Masonic Lodge later to be known as Union Lodge No.108.

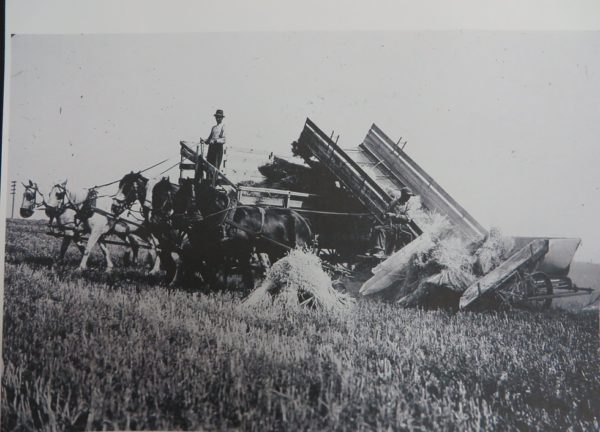

In the Brookdale district prior to 1907, two members of the community: H. C. Smith, station agent, and R. B. C. Thomson MD, being Masons themselves and there being no lodges closer than Neepawa and Carberry, decided to canvass not only the Brookdale district but the surrounding districts, Moore Park, Justice, Oberon, and Wellwood, to find enough interested people to form a Masonic Lodge. This was done and the following persons besides the original two expressed a desire to join: Mr. Beeman, Mr. Hughes, Mr. Phil McRae, Mr. H. Leslie, Mr. T. Ballantyne, and Mr. H. Allen.

Their application to the Grand Lodge of Manitoba was approved and the D.D.G.M. of District Number 2, a Mr. McIntosh, was instructed by the Grand Master of Manitoba to institute a lodge on July 26, 1907, to be known as Union Lodge No.108. The word ‘Union’ recognized that several districts were represented in the membership.

At the first meeting July 26, 1907, a total of four petitions for initiations were received, besides the eight founding members. Before the end of the following year, 14 more petitions were accepted.

The first year was a very successful one with Grand lodge approving the work done and the progress made. Accordingly on June 10, 1908, a charter was granted and the lodge officially designated as Union Lodge No. 108 AF & AM.

The lodge, on the authority of the Grand Master Most Worshipful Brother H. J. Pugh, instructed the District Deputy, Right Worshipful Brother William Dickie of District No.2, to officiate at the constitution on the above date, of Union Lodge No. 108.

The lodge, not having a permanent building, held its meetings in the upper classroom in the school, from 1907 until 1916.

According to a Brookdale history book, this building was originally a bake shop, then a harness shop. In 1916, the building became available and was acquired by the Lodge for the sum of $470, which included some repairs. After extensive alterations, the upper part was used as a lodge room with an outside entrance, and the ground floor was rented out, providing a small source of income.

In 1928 the lower hall was taken over for a lunch room and recreational purposes. It was also made available to the community or groups such as the Red Cross and 4-H, free of charge. The “no charge” rule was imposed by the municipality, and in return the hall was not liable for property taxes. This policy ended several years ago.

The Order of The Eastern Star has had the facilities made available to its members since its founding in 1953.

From the years of its establishment in 1907, the lodge has had a steady growth in membership, due in part to the fact that it was the closest lodge available for several districts.

Membership has remained fairly constant over the years, with enough new members coming in to compensate for those moving away or passing away.

It should be mentioned here, that the lodge has appreciated the fact that the majority of the members who have moved away, have maintained their membership in their Mother Lodge.

In all jurisdictions, the smaller lodges, including ‘Union’, are having problems keeping their lodges going due to the high cost of taxes, heat and light. There are more demands too, on the members’ time and money in the community. Union Lodge, we hope, will be able to cope with these many problems. We have survived our 50th, our 75th, and hopefully look forward to our 100th anniversary.

We are indebted to many members down through the years who have contributed to the lodges’ well being. (The foregoing was written by R.M. Mikkelson for the Brookdale Centennial Celebration book)

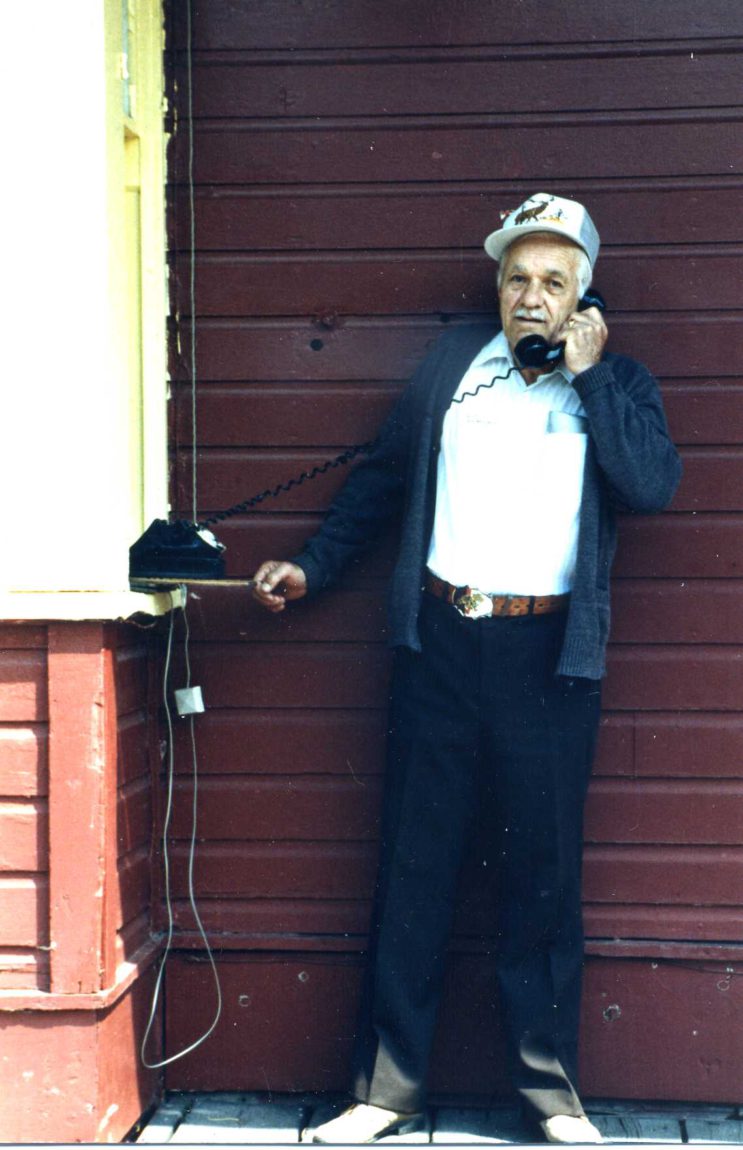

In 1986 Union Lodge decided to give up their charter as an active lodge on the Registry of the Grand Lodge of Manitoba. R. W. Bro. Alvin G. Hewitt was the District Deputy Grand Master of District 2 at the time, he and several brethren of the District decided to have the lodge moved and placed as a working lodge on the street of the Manitoba Agricultural Museum. Negotiations got under way with the Board of the Agricultural Museum and with the Board of General Purposes of the Grand Lodge of Manitoba. An agreement was reached and a small group started on the project of fund raising. The Masons of Manitoba were most generous in their support and in a very short time the building was moved from the Town of Brookdale to the grounds of the Manitoba Agricultural Museum.

It took many hours of work by a few dedicated Masons to strip the old siding from the building, place new siding, pour a new foundation and strip coats of paint from the interior surface. The lodge room was repainted as near as possible to the original colour, the carpet on the floor of the lodge room was donated courtesy of Strathcona Lodge No. 117 at Belmont, Manitoba, which amalgamated with Glenboro Lodge No. 48 on 30 June 1988.

On July 25, 1992, Most Worshipful Brother Morley J. McKay and Grand Lodge officers formally dedicated the building and placed the bronze plaque on the outside wall near the front entrance door.

An Emergent Communication was held 13 July 1994 under the guidance of Most Worshipful Brother W. Bruce Porter, Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Manitoba, for the sole purpose of reconstituting the Lodge as “Union Historical Lodge No. 108” on the register of the Grand Lodge of Manitoba. The original Charter of Union Lodge, properly endorsed, now hangs in this building.

On July 13, 1994, Union Historical Lodge No. 108 was opened in the Three degrees of Masonry by the Grand Master, M. W. Bro. Bruce Porter and his Grand Lodge officers for the purpose of re-instituting and re-constituting Union Historical Lodge # 108. This service was performed in a most capable manner by those officers.

Union Historical Lodge No. 108 meets in this building on the last Friday of May and the last Friday of September each year. Any Mason in good standing in any Lodge in the world, providing his jurisdiction is recognized by the Grand Lodge of Manitoba, may join this Lodge. The fee is a once in a lifetime fee of $50. The fees are used to help in maintaining the building. The fee is payable to: Union Historical Lodge No. 108 Attn.Secretary, 52 Tupper Street South, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, R1N 1W6.

I shall pass through this

but once,

If, therefore, there is any kindness

I can show,

or any good

I can do my fellow being

Let me do it Now!

Let me not deter

Or neglect it

For I shall not pass

This way again.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are the tassels hanging in each corner of the room?

They represent the four Cardinal Virtues, Temperance, Fortitude, Prudence and Justice. Temperance reminds one to keep excessive appetites within due limits. To be temperate in all your actions. In days past, in some lodges, it meant abstinence from alcohol. Fortitude suggests we should bear the ills of life with becoming resignation, do not let life wear you down. Prudence is the true guide to human understanding, be courteous with words and speak with propriety. Justice suggests we should keep our feet firmly planted on the ground in an upright manner. Treat all people equally and with respect.

What does the letter G represent?

The letter G represents God, the Grand Geometrician of The Universe and usually hangs over the Volume of The Sacred Law or Holy Bible. Each Mason must believe in a Greater Power, atheists are not accepted into the fraternity.

Why are the square and compasses on the walls?

They are indicative of the working tools of an operative mason and in the Lodge the square remind us to square our actions by the square of virtue and the compasses to remind us to practice brotherly love, relief and truth. In our world today many are concerned about the bitterness and hate that is so prevalent in human affairs. About the weakening of moral standards, disrespect for the laws of society and for the rights of others. Everywhere there are individuals and groups that are striving to maintain decent standards in society and to preserve those ways of life that are founded on justice and integrity. Freemasons are also concerned about these things, and hope to add their influence in protecting the honour and dignity of human life.

Freemasonry stands for kindness in the home; courtesy toward others; dependability in one’s work; compassion for the unfortunate; resistance to evil; help for the weak; support for education; and above all, a reverence for God and love of fellow man.